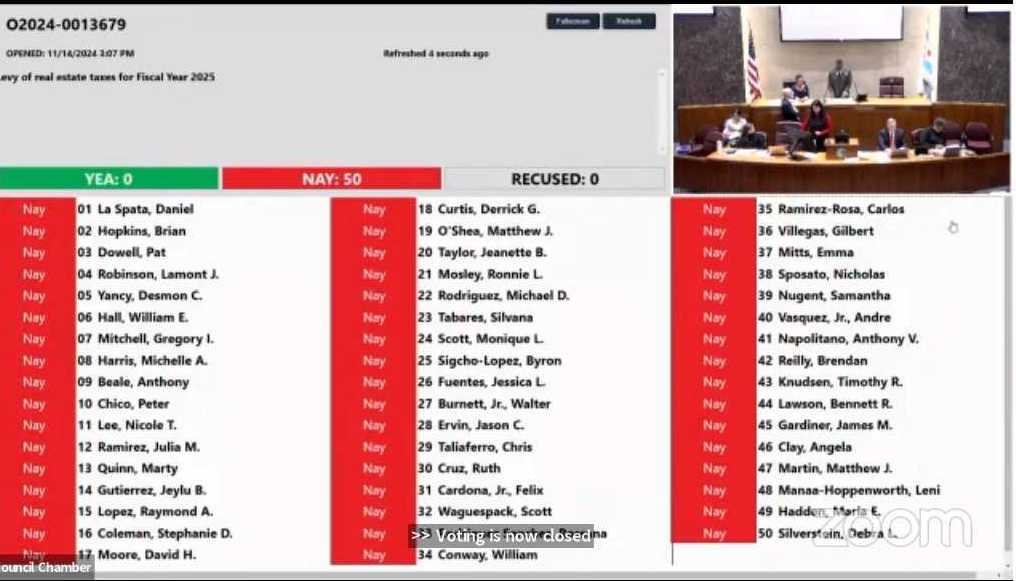

Last week, Ald. Vasquez and 29 other City Council members signed a letter calling for a vote on the Mayor’s proposed $300 million property tax increase. Yesterday, in a special meeting of City Council, all 50 alders voted against the increase.

This unprecedented unanimous vote regarding a proposed revenue ordinance was a clear rejection of a significant property tax increase. But it still leaves City Council and the Mayor’s Office with a $300 million dollar gap to solve.

How do we solve that $300 million dollar gap? Here are some of the options that we’re considering as Ald. Vasquez works with City Council members to create a more responsible, balanced budget:

- Structural Revenue: revenue other than property taxes that the City can raise to offset the gap;

- Temporary funds: temporary funds from the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) federal stimulus money or other grants that the City may be able to draw upon to cover the gap until the funds expire, but are not a long-term solution;

- Efficiencies: additional spending cuts that may be able to save the City money without negatively impacting services that neighbors depend on.

- Debt restructuring: the City has a history of being penny-wise and pound foolish, and a restructuring of pension and bond debts that save us money over the long run by reducing future borrowing costs are important to analyze,

Structural Revenue

When looking at alternate forms of structural revenue, our priority is to find sustainable revenue streams that are progressive rather than regressive.

The difference between progressive vs. regressive revenue comes down to who is most impacted. With progressive revenues, those who have more pay more, e.g. the fair tax, which would have established a graduated tax. Regressive revenue is any revenue that takes a larger percentage from low-income groups than high-income groups––which includes flat fees. While flat fees might be the same for everyone, they have a higher impact on those who earn less income than on those who make higher incomes.

Here are some of the alternate revenues we are exploring:

- Increasing luxury taxes on parking garage and valet parking fees, as well as amusement (e.g. streaming services)

- Increasing houseshare surcharge tax for people visiting Chicago and renting AirBNBs or VRBOs: the bulk of these funds would be dedicated toward gender-based violence initiatives

- Adding tolls for cars driving into the city, or driving in the Central Business District

- Taxing Delta 8/THC and/or hemp-derived products, which we are currently working on;

- Increasing the fees that polluting industries pay after they violate pollution thresholds;

- Increasing the number of citywide speed cameras, while ensuring equitable placement

- Expanding the Smart Streets pilot, which tickets people for parking in bike lanes or bus lanes, and crosswalks

- Indexing existing city fees and consumption taxes to inflation, including garbage, liquor, water bottle, and large truck city stickers.

- Considering a smaller increase in the property tax rate, which would then be indexed to inflation for future years. The City’s analysis shows that if Chicago had increased property taxes by the CPI since 1977, it would have ended up with the same property tax levy in FY23, without the City having sold off City assets (e.g. parking meters, parking garages, and the Skyway).

We’re also exploring temporary forms of revenue that may be able to tide us over while we look for more sustainable structural revenue streams––for example, the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) funds, the COVID relief grants for municipal government paid out by the federal government, state grants and local and private grants. While it may be possible to draw on these funds to cover some of this year’s budget gap, it is not a long-term solution. Once those funds run out, we will still be left with the same deficit problem, so it’s important to prioritize long-term, sustainable solutions.

Efficiencies

As we look for more revenue, it’s also important that we consider areas where the City can save on spending. The Mayor’s proposal had departments across the City cut their budgets by 3% each, and 744 vacant positions have been eliminated to save on projected workforce costs. However many Council members, including Ald. Vasquez, don’t believe that some of the Mayor’s current proposals––like cutting Consent Decree positions within CPD––are a wise choice.

When we look at efficiencies, we’re typically looking at two things: workforce reductions, and program reductions.

Workforce cuts aren’t limited to layoffs. It can also take the form of furloughs––cutting the amount of hours or days that city employees work––or eliminating vacant positions. Generally, we are opposed to both layoffs and furloughs, because they usually result in residents paying a similar amount in taxes for less service.

Eliminating persistent vacant positions can be a helpful way of reducing the workforce budget without requiring layoffs and furloughs. But whether there are additional vacancies that can make a big enough dent in the budget gap remains to be seen. It’s also worth noting that the majority of these vacancies are within Police, Fire, or other public safety departments––though these vacancies make up a minor percentage of those departments’ overall budget.

The other type of efficiency to consider is program reductions: auditing the budgets of individual departments to make sure they are running efficiently and effectively. Ald. Vasquez has been advocating for a city-wide audit since his first term in office, starting with our largest department and working our way down.

Let’s look at the Chicago Police Department as an example. CPD is the highest-spending city department, making up about 42% of the city’s FY25 local fund-based expenditure on purely personnel-related costs. When you look at total appropriations that are locally funded, CPD spending is 30%. The amount of overtime pay in the CPD budget has ballooned over the years, as their job functions have expanded. Currently, officers are being asked to address issues like illegal parking and homelessness in addition to their main function, and as a result, they are being overstretched and increasingly burning out.

A great example of this is event security: currently, CPD overtime costs for external events are not always reimbursed fully by the companies hosting those events. Another option to explore may be to require event organizers to cover their own security, and limiting CPD responsibility to collaborating on planning and perimeter checks.

Public safety is a hugely important role, and worth spending money on. But we need to look into what police are being asked to do and evaluate whether some of those services might be more efficiently covered by another department, so they can focus on their core function: investigation, apprehension, and emergency response when appropriate. We also need to examine how they are performing those functions, and what changes need to be made in order to minimize the amount the City is paying yearly in legal settlements––which last year cost the city over $80 million.

That level of accountability isn’t just necessary for the City’s largest department––we have to extend it to every other department, too. We literally owe it to Chicagoans to make sure we are using their funds efficiently and effectively––from scrutinizing staffing and spending of the Mayor’s Office, to assessing how middle management functions across departments. Independent audits to evaluate how the city can operate more efficiently as a whole is a crucial step in setting us on a path to a more stable and sustainable financial future.

Restructuring Debt

It’s no secret that a significant portion of the City’s budget goes toward pensions. But contrary to popular belief, it’s not pension payments that’s driving the increase in spending on pensions: it’s pension debt.

Past administrations were not paying off Chicago’s pensions at the appropriate level. Pension debt continued to grow, which meant that the interest grew as well. This led to deficits that got so large that the City started selling off properties such as the parking meters and the Skyway to cover the gap. But these were short-term solutions, and we can see now the long-term impact they’ve had on Chicago.

In order to meet our legal obligations and retain the City’s good financial standing, we must pay our advanced pension payments. But we can look into options to restructure that debt, like pension obligation bonds (POBs). Instead of taking on new debt, POBs transfer pension debt to bond debt, which carries a lower interest rate. While this option won’t fix this year’s budget shortfall, it is worth considering as we work to correct decades of financial irresponsibility without relying solely on property taxes to cover the gap.

We Want Your Feedback!

Do you have thoughts or ideas on how we should approach this year’s budget problem? Fill out our 2025 Budget Survey to let us know what alternative revenues or efficiencies you think the City should consider. Please submit your thoughts by Monday, November 18th. We’ll be presenting on some of the initial highlights in our Budget Briefing on Thursday, November 21st from 6-7:30pm. Register at bit.ly/40thbudgetbriefing!